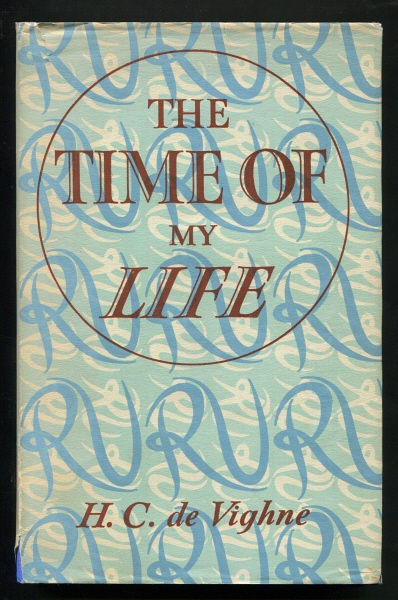

The Time of my Life – the autobiography of a young immigrant in late 19th century USA and his later working life as a doctor in Alaska

I didn’t set out to read this autobiography, subtitled ‘A Frontier Doctor in Alaska’, from cover to cover but in cataloguing it I just got hooked. First published in 1943 the author, Harry C. de Vighne, presented a collection of snapshot-narratives of late nineteenth century USA at a fascinating time in its history.

In cataloguing our stock I like to help the potential buyer by giving them an indication of the content of our non-fiction titles. I am convinced that, as well as those who buy knowing the author and title, there are those who buy speculatively never having heard of a title before but who are interested in the subject matter if only they are told what it is. If I can give sufficient details about the content then I might persuade those potential readers to purchase a book they didn’t know existed.

The jacket blurb is often very useful guide to the content although some publishers do tend to go over the top with their descriptions. This edition was published in 1946 by the Reprint Society, an era when they rarely included such promotional blurb. I flicked through the pages intending to pick out a selection of salient points, as one does, and it wasn’t long before I was hooked. The variety of events the author experienced as a child and young man was extraordinary.

The account opens with the author as an eight-year-old orphan in New York. He remembered living in Havana and moving with his parents to New York about 1884 when shortly after their arrival both his parents died. He was briefly taken in by a friend of his father but his potemtial step-mother made it plain that his presence was unwelcome and he soon ran away to live on the streets of Bowery.

He was taken under the wing of Shorty McGurk, a friendly Irish ruffian who appears to have been hired muscle and a sort-of local godfather who fed, sheltered and clothed him in return for errands and odd jobs. He spent two years with him learning the way of the streets and Bowery-Irish-English with the addition of his Cuban accent, until one day Shorty was taken to hospital where he died.

By this time Harry knew his way around New York’s lower east side and he obtained work as a news boy selling papers on the streets. At the age of twelve when a successful newspaper seller with a wealth of urban nouse he must have had an off day because he was captured by the truancy board. Within a few days he and a group of similar orphans were escorted by train to Iowa where on arrival he was selected in a way reminiscent of the children evacuated in wartime England. He was informally adopted by a kindly farmer, who described himself to him as his new grandfather, and his wife.

Grandfather, originally a native of Kentucky, was an unreconstructed rebel and a veteran of Quantrel’s (sic) Raiders. Harry had been lucky in his selection and was regarded as a family member, for the first time in his life having a decent room to himself, a feather bed, privacy, books and leisure time. At the time of his arrival work on the farm was slack, spring planting finished and harvest not yet begun and there were many new discoveries about country life to be made by a city boy.

For someone used to the noise and bustle of the big city however there was a limit to the attractions of learning where milk comes from, gathering eggs, splitting kindling and chasing rabbits from the garden. Even with proper schooling and an abundance of food, after a couple of years the silence at night still seemed unnatural. His new ‘grandparents’ started to realise that Harry had not been born to farm but they hoped that in time he might accept this way of life. He might have done, had it not been for ‘Uncle’ Ike.

Ike, one of grandfather’s surviving children, was a lawyer and had been admitted to the bar with a practice in the frontier town of Deadwood. His letters home and occasional copies of the local newspaper fired Harry’s imagination and his youthful lust for adventure and excitement. This eventually got the better of him and he ran away from the Iowa farm to Deadwood and Uncle Ike and Aunt Julia.

He describes 1890 Deadwood at some length, a ‘brazen hussy, ageing but still voluptuous’ with nearly three thousand people wedged into the narrow valley. All supplies were freighted in on great wagons with dry squealing axles trailing behind ox-teams. The Bella Union and Gem dance halls still flourished and a large number of men carried guns openly swinging on a belt. There was some hard drinking by miners and railroad men which often led to fights, and smouldering animosity between the soldiers of Fort Meade and blanket Indians from the reservations.

As a fourteen year old he seems to have been accepted by the small parties of Sioux who would camp on the outskirts of the town, with whom he exchanged candy and tobacco for scraps of tribal information and he must have picked up the language as well. He and Aunt Julia accompanied Uncle Ike when he was called to Chadron on court matters, about two hundred miles south, and was there when the massacre at Wounded Knee took place. He describes a visit to the Pine Ridge Reservation and the site of the ‘battle’ where the dead were still lying amongst the blown down tepees and personal effects.

On return to Deadwood he picked up his schooling again and his study of the law. As a acknowledged member of Uncle Ike’s family he was welcome at a number of social gatherings but there was often some question as to his exact relationship. To impress a girlfriend he made up a background for himself which reflected badly on Aunt Julia, word of which got back to Uncle Ike and within a day or say he was sent back to grandfather’s farm.

He broke his journey at Omaha and earned his keep selling newspapers again. Seeing an advertisement for ‘mule-skinners’ at $30 per month he investigated and was taken on as a mule team driver for the railroad builders near Laramie. After a while there he teamed up with a fellow driver and travelled the railways with him as a hobo for three years.

One rainy night in St. Louis he saw a well dressed man obviously the worse for drink trying to negotiate a bridge across the Mississippi. When he offered him help he agreed to the man’s request to see him home. The drunk, who turned out to be a doctor, invited him to stay the night and in the morning offered him the work of cataloguing his library.

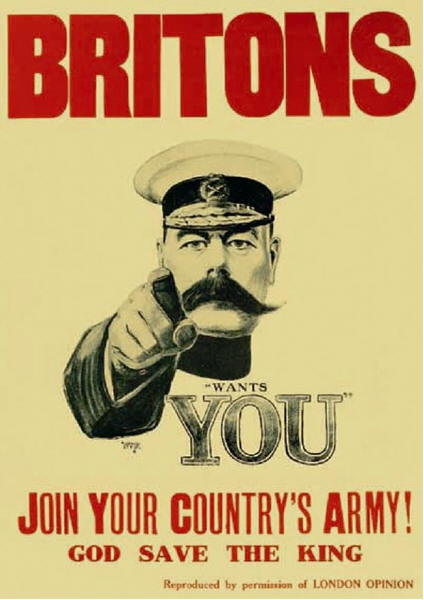

Browsing some of the library books Harry became interested in medicine and the doctor helped him become a medical student. He interrupted his studies to work his passage from Boston to Liverpool tending the cargo of cattle before returning to New York, then joining a vessel gun-running to Cuba. Back in New York again he recognised the Deadwood Sherrif, Seth Bullock, who gave him a reference to join Roosevelt’s Rough Riders who were gathering at San Antonio en route to Cuba. By the time he reached San Antonio they had left and instead he picked up his medical studies again at the South-Western Insane Asylum there, from where he eventually obtained a place in a medical school in San Francisco.

On graduation he became an extern at the City and County Hospital and then moved to Alaska to take up a government medical appointment, spending the next thirty years (and the next 100 pages) fulfilling the sub-title of the book, an equally enthralling narrative about the early years of the development of that state.

As a matter of course when cataloguing I check to see what other copies of any unusual book are being offered. This title does not seem to be scarce as at the time of writing there were fifty-seven copies being offered for sale but none of them had a description of the content. One does now!