The 1st February 2017 will be the 75th anniversary of a tragic incident which took place in Victoria Road, Lowestoft in 1942 during WW2, when a mother and her two children were killed by a German bomb. Their deaths, however, led to the installation of the public ‘Cuckoo’ crash alarm of air attack and the saving of countless other lives. That fact alone is, I believe, worthy of commemoration.

I first discovered the background to this event when editing Lowestoft resident Alfred J. Turner’s letters to his son (my grandfather) about the daily WW2 events taking place in the front-line port of Lowestoft (see ‘Letters From Lowestoft’). The peace-time fishing port and seaside holiday resort had become home to what would eventually become five Royal Navy bases including the main drafting base of the Royal Naval Patrol Service, the army with a presence to brigade level to protect the potential invasion coastline and the surrounding countryside with a high density of fighter and bomber airfields.

Click for larger image

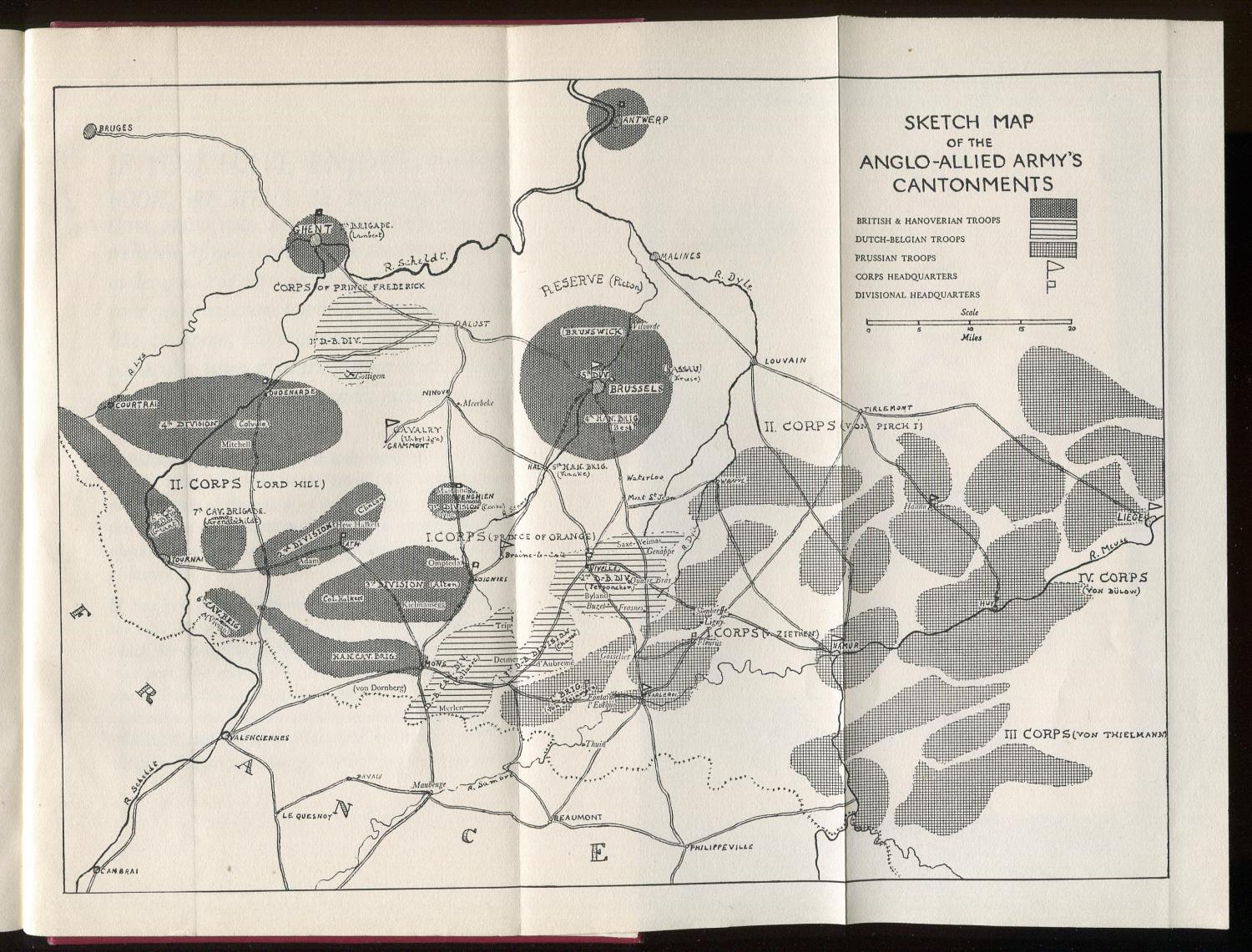

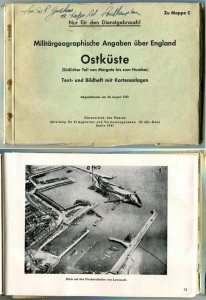

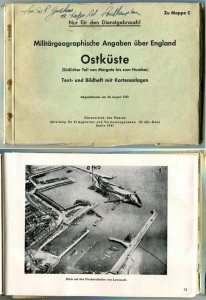

At that time Lowestoft still maintained many of the specialist support skills that an active peacetime fishing fleet needed with ship building and repair yards, dry-docking facilities, chandlers, etc., all of which were in high demand as the needs of the WW2 warships had to be met. The military and naval presence and their support services led to the town being a genuine and frequent military target (as well as an occasional target of opportunity) for the German Luftwaffe, as can be seen in the 1941 German military’s guide to British East Coast targets (right)

In Alfred J. Turner’s letters he makes frequent reference to ‘crash’ alarms of air attack as well as the wailing siren type. He does not explain the crash alarm but the inference is that this was a limited, private warning of imminent air attack to the town’s industrial and business areas, in advance of the standard air raid ‘alert’ siren. It is known that a number of the factories and workshops had rooftop lookouts in place to give warning to their workforce of the approach of low-level enemy raiding aircraft, most of which would have been below the main radar network and so would not have triggered a full ‘alert’. That these warnings were shared by some means to trigger a ‘Crash’ alarm is not surprising but how is unclear, although he does make a reference to the ‘destructor buzzer’.

The ‘town destructor’ was a refuse disposal system in the area of the junction between Denmark Road and Rotterdam Road. The destructor furnaces burned the town’s refuse which may originally have been the fuel source to make electricity for the town’s long since disappeared trams, although the original tram sheds remain in Rotterdam Road to this day. It was in place at about the turn of the century and quite close to Lake Lothing although disused by the time of WW2. Any remaining destructor chimney would have been an ideal spot on which to fix an audible warning device to the industries along the Lake Lothing waterfront. As it is known that sounds travels well over water any audible warning would probably have also reached the town centre.

Early warning by the private ‘Crash’ alarm system of hit and run air raids meant that the workers in the shipyards and other industrial units had the chance of taking shelter before any bombs were dropped. Sadly this was no help to the general public as the warning did not reach them except by word of mouth.

The entry in ‘Letters from Lowestoft’ for Sunday 1st February 1942 includes the following:

“At 11.30 am there was heavy gunfire and apparently also bombs. Mother and Annie Rix went to the cellar for a very few minutes. We were not at church on account of bad going, snow and very slippery roads. Bombs were dropped near the Lord Nelson and a woman and two children killed, we hear, and some damage to property. The siren went about 6 or 7 minutes after everything was all over.”

Ford Jenkins’ ‘Port War’, published in 1946 as a mainly pictorial record of WW2 as experienced by Lowestoft, records in his summary of air attacks on Lowestoft, page 76:

“11.30am 1st February 1942, 4 HE bombs, Hilltop, Victoria Road and Heath Road, 3 civilians killed, 1 injured”

….and on page 29 of Port War there is a photograph (reproduced below) of Victoria Road close to the junction with Heath Road, with the caption:

“On a quiet Sunday morning, the 1st February 1942, the family of a workman who was himself taking shelter, was killed by a lone raider that bombed the Victoria Road vicinity. The workmen had been warned by the private ‘Crash’ system that had been installed at their shipyard but, at this time, there was no public ‘Imminent Danger’ warning system. The fatality led to the men demanding that the ‘Crash’ should be made generally public and within twenty-four hours Lowestoft had the first such system in the country.”

In fact it seems it took a little longer than that and was helped along by the threat of civil unrest according to the entries on 3rd February in ‘Letters from Lowestoft’:

“Warnes the builder in yesterday afternoon told me ….. the Town was very upset and workmen were striking on Thursday if the authorities refused to give Crash warning.

“The Rector … came in to know if we took the Daily Express as there was a long descriptive article in it describing Lowestoft as Hell Fire Corner instead of Dover which has held the name for several months.

“He said also there was severe criticism going on about the lateness of the sirens, the absence of gun fire and fighters and that much talk of a general strike by workers if no Crash warning was to be given. That ‘Authority’ at Cambridge was not opposed to it but our Mayor thought it would make people jittery and he opposed it. That the Mayor was told to sack the ‘Conchies’ at the Town Hall and that his son was to resign from his Observer Post.

“The poor woman and her children killed last Sunday was the wife of a worker on a shipyard and was always the first to take her children to a shelter when the alert went. There was no alert but a Crash on. The man took shelter and his family were killed. This was the base of all the trouble.”

This is followed by a further entry on 4th February:

“I hear semi-officially the shipwrights and also the railway men had two separate meetings about the siren situation, that the Mayor attended the Railwaymen’s and on starting to address them was told they did not want to hear him, that they would do the talking. Subsequently the whole matter was taken to the Military and the ‘Commandant’ said ‘This is a military town in a prescribed area. I am above the Mayor and all civilians. If there is any strike I shall not continue any efforts for the latter as I have been hitherto’. So that was that. There was no strike. But we are to have the ‘Crash’ warning and now each day at 9.00am the old Destructor Buzzer blows the ‘All Clear’ and we are told that as soon as possible it will sound “Cuckoo” for a Crash warning.

The advantage of a public ‘Crash’ alarm that sounded like a cuckoo was that it was instantly recognisable and did not need time to wind up to a certain level of sound as did the standard air raid siren. It did not replace the siren but was in addition to it.

I am satisfied that the family involved in the bombing on 1st February 1942 was called Bessey. The 1939 Register compiled for the issue of identity cards, as held by the National Archives, records as resident at 5 Hill Top, Kingley (sic) Run, Lowestoft:

Hilda E.M. Bessey, born 1906 (mother)

Peter William Bessey, born 1931 (son)

Pamela K. Bessey, Born 1937 (daughter)

Stanley W. Bessey, a shipyard worker, born 1900 (father)

Hill Top was a small group of residential railway carriages on a siding of the railway line that ran parallel to Victoria Road, next to Kirkley Run, Lowestoft. Older residents will probably remember the level crossing at this junction even if they don’t remember the carriages.

Kirkley Cemetery lists the following burials on 6th February 1942 in plot K/V/204:

Hilda Emma Mary Bessey, aged 35 years, wife of S. Bessey

Peter William Bessey, aged 10 years, a scholar

Pamela Kathleen Bessey, aged 4 years, an infant

…and a further burial is poignantly listed in the same plot over thirty year later, on 28th March 1973:

Stanley William Bessey, aged 72 years, a pensioner

The Mayor’s summary of the air raids on the town included the following extract from an address he gave at The Odeon on 6th May 1945:

“The first ‘Cuckoo’ – instant danger – was at 9.37am on 20th March 1942 and the last at 9.15pm on 22nd March 1945. The total number of ‘Cuckoo’ (soundings) was 628,” so in fact it took about 6-7 weeks for the installation of the Cuckoo alarm, not the following day.

It strikes me as suitable that there should be some form of recognition of the loss suffered by this family. The sad deaths of Mrs. Bessey and two of her children were the trigger to the subsequent installation of the ‘Cuckoo’ immediate danger ‘Crash’ alarm system to the general public of Lowestoft, which must have saved many other lives. There may have been other family members who survived and if they can be traced it would be interesting to find out their wishes.